| May 19, 2013 | Contact | Calendar | The Mix | Archives |

The most surprising and infrequent thing in Eudora Welty stories is when something actually happens. Mostly the stories are like photographs with the background story filled in or with the stream of consciousness of one of the characters written out. Why I Live At The P.O. was supposedly written as the back story to something she saw: a woman ironing at the post office.

The most surprising and infrequent thing in Eudora Welty stories is when something actually happens. Mostly the stories are like photographs with the background story filled in or with the stream of consciousness of one of the characters written out. Why I Live At The P.O. was supposedly written as the back story to something she saw: a woman ironing at the post office.

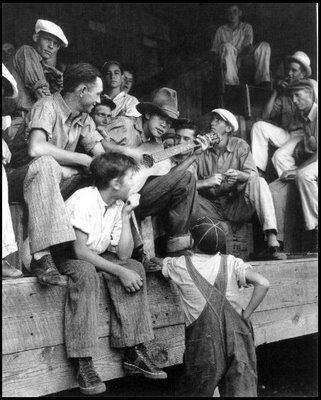

This is one of her photographs. The Hitchhikers could start with this picture and end with the standing boy (make him black) getting the guitar after man on the left kills the man with the guitar because he was tired of the way he just went on and on. Add a depressed third party observer, the salesman, who is given to semi-delusions and reverie ("On the road he did some things rather out of a dream. And the recurring sight of hitch-hikers waiting against the sky gave him the flash of a sensation he had known as a child: standing still, with nothing to touch him, feeling tall and having the world come all at once into its round shape underfoot and rush and turn through space and make his stand very precarious and lonely.") That story is unusual in that there is physical movement; mostly life happens in the minds of her characters. She is a master of the language of dreamy consciousness. Other stuff is just fun: "Do you think it wise to disport with ketchup in Stella-Rondo's flesh-colored kimono?" I says. So far my favorite of the stories is A Memory. My father and mother, who believed that I saw nothing in the world which was not strictly coaxed into place like a vine on our garden trellis to be presented to my eyes, would have been badly concerned if they had guessed how frequently the weak and inferior and strangely turned examples of what was to come showed themselves to me. |